We’re Not Learning Anymore

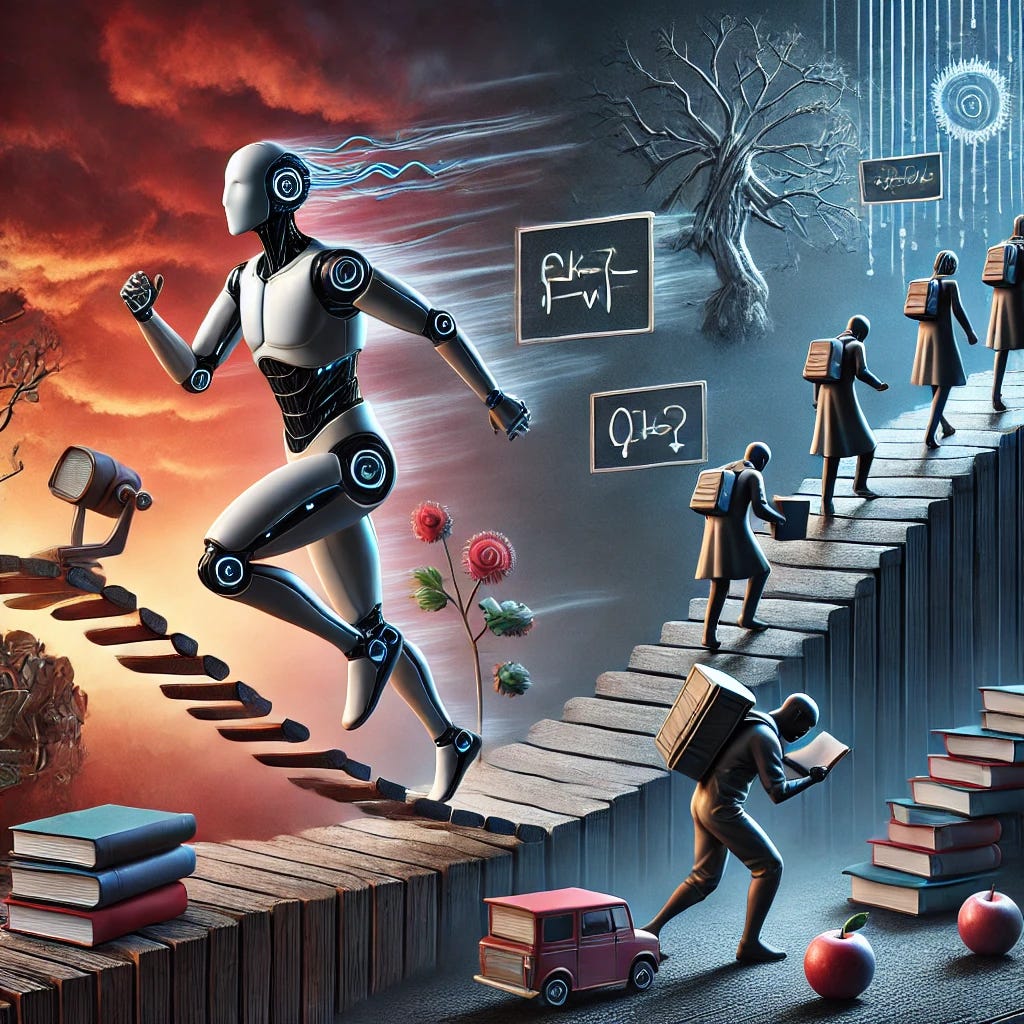

How AI Skips the Hard Part

Most people think AI is making them better, but the definition of “being better” has changed drastically.

Their writing sounds cleaner.

Their work looks more polished.

Their results arrive faster.

What they do not notice is what they skipped.

AI now helps you write before you struggle.

Design before you practice.

Solve before you understand.

That feels like progress.

But learning used to start with being bad.

Awkward drafts.

Wrong turns.

Embarrassing first attempts.

When AI removes that phase, it does not just save time.

It changes what learning is.

And once you lose the ability to be bad at something, getting truly good becomes much harder than it looks.

Being Bad Was the Entry Point

Every skill used to begin with visible failure.

Awkward sentences.

Clumsy designs.

Broken code.

Wrong notes.

Psychologists studying skill acquisition have long shown that early failure is not a side effect of learning. It is the mechanism that drives it (Ericsson et al. 1993).

Being bad gave you feedback.

It gave you texture.

It gave you a sense of progress that came from effort, not output.

AI Skips the Ugly Phase

AI changes the sequence.

You can now produce something polished before you understand the process behind it. A paragraph that sounds confident. A layout that looks professional. A function that runs.

The output looks finished.

The learning is not.

Research on automation and skill development shows that when systems perform core steps for users, people often fail to develop deep mental models of the task itself (Bainbridge 1983).

You get results without apprenticeship.

Why This Feels So Good

This shift feels empowering at first.

You avoid embarrassment.

You avoid frustration.

You avoid wasting time on obvious mistakes.

Behavioral research shows that people strongly prefer tools that reduce early negative feedback, even if long-term mastery suffers (Risko and Gilbert 2016).

AI removes friction.

Friction used to teach.

The Confidence Trap

When you never see your own bad versions, confidence becomes unstable.

You feel capable while the system is helping.

You feel lost when it is not.

Studies of over-reliance on decision aids show that people can confuse tool-assisted performance with personal competence, leading to sharp drops in confidence when support is removed (Dietvorst et al. 2015).

You do not build trust in yourself.

You borrow it from the system.

Creativity Suffers Quietly

Creativity depends on bad drafts.

The first version is supposed to be wrong.

The second is supposed to be messy.

The third starts to feel like yours.

When AI smooths early drafts too quickly, creators often skip the phase where ideas surprise them. Research in creative cognition shows that constraint, delay, and error are essential for original insight (Stokes 2006).

Good output appears faster.

Original thought appears less often.

Skill Becomes Thinner

This does not mean people become worse.

They become narrower.

They can operate tools.

They can edit results.

They can steer outputs.

But fewer people can build from zero.

Fewer people tolerate not knowing.

Educational researchers warn that systems which optimize for correctness too early can reduce exploratory learning and long-term transfer of skills (Kapur 2008).

You get competence without resilience.

Why This Matters Outside Work

This pattern does not stay in professional life.

It spills into hobbies.

Learning.

Self-image.

When people are never bad at something, they stop starting new things. They avoid domains where AI cannot help yet. They choose safety over growth.

Failure used to be temporary.

Now it feels optional.

And that changes behavior.

What We Might Lose

Being bad was not just a phase.

It was a signal.

It told you where effort mattered.

It told you when you were improving.

It told you that mastery was earned.

AI does not remove the need for learning.

It removes the pain that made learning meaningful.

AI is not making people less capable.

It is changing how capability forms.

When systems erase the awkward phase, they also erase the patience, humility, and persistence that came with it.

Being bad used to be how you knew you were learning.

If we lose that signal, we may still get good results.

We just may not know how we got there.

And that is a different kind of progress than we are used to.

References

Bainbridge, L. (1983). Ironies of automation. Automatica, 19(6), 775–779.

Dietvorst, B. J., Simmons, J. P., & Massey, C. (2015). Algorithm aversion. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 144(1), 114–126.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406.

Kapur, M. (2008). Productive failure. Cognition and Instruction, 26(3), 379–424.

Risko, E. F., & Gilbert, S. J. (2016). Cognitive offloading. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(9), 676–688.

Stokes, P. D. (2006). Creativity from constraints. Springer.

Ai should be a tool only to use when appropriately needed. Not as the primary source.

Generally when I write or express something here in Substack, it’s always from the heart and written without that tool. Probably something I should use a little extra though. 🤓😊

Have an excellent day.

Thank you for sharing.

I think AI lowered the barrier to get into specific domains of professions.

Having been in tech over two decades, I was able to pivot with every new tech throughout my career. Because I had the fundamentals and the ‘actual doing of the grunt’ of the work.

You can’t retrofit experience onto tech. It doesn’t work that way.

Tech changes, then what do you have to fall back on; zilch.

I use AI as an enhancer not as a replacement. I highly recommend it!!